Steven Spielberg is a huge director. Arguably he's the biggest, most successful, and well-recognized one in history. His reputation looms large, with individual films such as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Indiana Jones, and Jurassic Park all pop-culture staples. Spielberg’s detractors also claim he goes for “big” emotions, his films having a broad sentimental streak that softens his movies for general audiences.

But Spielberg’s massive success often overshadows his genuine craft and diverse body of work. His two hits of 1993 – Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List – demonstrated his split sensibilities of blockbuster entertainment and serious prestige pictures, and their success enabled Spielberg to found DreamWorks and produce more challenging (but still entertaining) works like War of the Worlds, Minority Report, Saving Private Ryan, Catch Me If You Can and A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

RELATED: Every Spielberg Movie, Ranked By Rotten Tomatoes

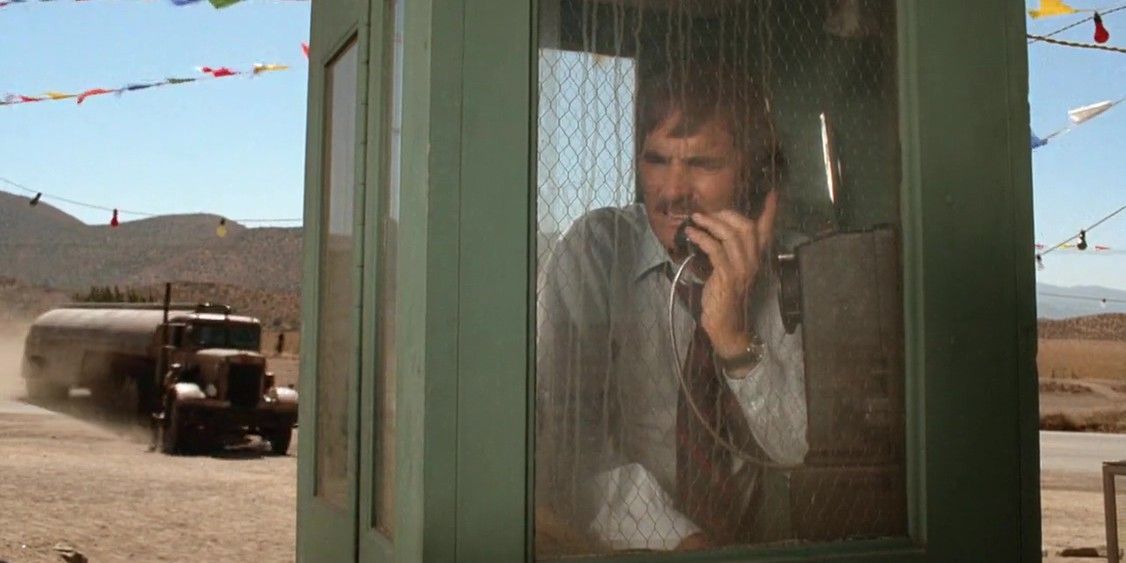

The upcoming West Side Story remake will be Spielberg’s 34th film, and after being delayed a year due to COVID-19, it will arrive on the 50th anniversary year of his 1971 directorial debut, Duel. After a few years working in TV, the 24-year-old Spielberg helmed Duel as a TV-Movie for Universal, which was impressive enough to warrant extra scenes and an international release. Compared to the ambition and heaviness of later Spielberg projects, Duel is enticingly stripped-down, the plot simply being that during a business commute through the Californian Mojave Desert, David Mann (Dennis Weaver) is pursued by a truck trying to kill him.

Duel remains locked into this simplistic conceit for its short 90-minute runtime. David never discovers a deeper reason for the truck stalking him along the road aside from the petty motive of having overtaken it. Duel never even shows the truck driver, recognizing that sometimes the scariest thing is what you don’t see, leaving the imposing Peterbilt 281 tanker truck as an ominous, even demonic, presence. Strapped to its rusted grill are several license plates, hanging like a warlord’s trophy collection of skulls.

Richard Matheson adapted Duel from his own short story of the same name, based on a real-life encounter that occurred on the day of the JFK assassination. Spielberg cut back the already sparse screenplay so David would have minimal dialogue in his isolated, and increasingly desperate, predicament.

This silence is punctuated by the roar of the truck, which startles David and the audience with loud honks and a guzzling engine that seems to roll around the Californian hills. Duel demonstrates that even an everyday menace can be terrifying – perhaps more so for how relatable it is – as Spielberg employs extended long-takes attached to David’s red car, tracing it as he speeds along and swirls off the road.

Duel shoots the truck from low angles, always emphasizing its daunting presence, and sometimes the camera will glide from David across the truck to demonstrate their comparative sizes. Although Duel also uses erratic edits to cut between David’s desperate uphill struggle on an empty tank as the truck approaches from behind, Spielberg pulling out multiple cinematic techniques to make Duel a tense and enthralling thriller.

Duel’s closest companion from Spielberg is his other ‘70s breakthrough hit, Jaws. Another Spielberg film, The Sugarland Express, rests between these two one-word-titled films, and is technically Spielberg’s actual “theatrical debut” which got him funding for Jaws. But although Sugarland Express also features car chases as two sympathetic felons try to reclaim their child taken by social services, the semi-comedic Blues Brothers type crime-drama is an outlier in Spielberg’s filmography. Duel and Jaws are much more similar, each featuring humble exasperated men facing off against incomprehensible beasts.

Jaws is a classic “Man versus Nature” blockbuster, the shark an abhorrent and dangerous element that Chief Brody (Roy Schneider) must conquer to restore peace. And Duel can also be viewed in these elemental terms of David battling the menacing Goliath of the truck. But like Jaws, there are also complex themes of masculinity and order and anarchy lying underneath. And while Jaws touches on the savagery of sea-life – striking unseen at residents of a cozy beach-town which sweeps such chaos under the surface – Duel’s truck is a product of industrialization, David literally choking on the exhaust fumes of this polluting oil tanker.

The truck representing some prehistoric age ties into the larger theme of masculinity. The protagonist is called David “Mann” after all. Early on he is listening to a male radio caller asking how to fill in a household census. He explains he is no longer “head of the household,” as his wife is the breadwinner while he does housework, but he’s embarrassed to admit this on the form. Gender roles are changing, and the truck represents the bullying, alpha-male ways that aggressively asserts its dominance on the road.

David himself exhibits a strained household dynamic, a phone call with his wife (Jacqueline Scott) revealing that when she was harassed at a dinner party last night David did not interfere. “If we talk about it we’ll just get into a fight,” David sighs to her, the conversation framed by an open laundrette dryer door. David is hemmed in by both sides, his indignant wife and the assertive truck, trapping him in circular motions unable to progress. Duel then symbolically shows David reclaiming his agency and breaking free of restricted mobility.

Family drama is a large, perhaps defining, characteristic of Spielberg’s filmography. E.T. has the kindly alien be a surrogate father for young Elliot (Henry Thomas), young Jamie (Christian Bale) searches for father-figures through Empire of the Sun’s WW2 Japan, and jet-setting conman Frank Abagnale (Leonardo DiCaprio) keeps trying to impress his father (Christopher Walken) in Catch Me If You Can.

War of the Worlds and Munich feature fathers trying to keep their kids safe in compromised worlds, and in A.I. family love is the desperate pitiful programming of child android David (Haley Joel Osment). Duel’s David is also stranded from his family, and has to struggle through the film just to get back home.

Duel is fairly distinct from these other entries and from Spielberg’s later big-budget filmmaking that reshaped the summer landscape. It fits into the ‘70s era of paranoid thrillers like The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, Marathon Man and All The President’s Men, David a sweaty everyman who gets pulled into a world with people out to get him. An inner-monologue has David commentate how you can feel safe and secure in a basically lawful world, but then one random act of violence disrupts this, “and it’s like there you are, right back in the jungle again.”

Duel may not tug at the heartstrings like later Spielberg, but it still gets the blood pumping. Spielberg is brutal and mean-spirited here in ways he rarely is, no reasoning or morality to be found in the open desert. Even Jaws concluded with Brody and Hooper (Richard Dreyfus) paddling back to dry land after the shark was finally defeated. Duel ends with David stranded in the desert, temporarily victorious but ultimately alone, his final fate uncertain. Duel’s minimalism lends itself to his poetic readings, but above all else it displays Spielberg’s impeccable directing and craft from the very beginning, Duel being a worthy debut to kickstart a long and winding road ahead.

MORE: Baby Driver 2 Can Take Influence From This Classic Car Movie