When Todd Phillips’ Joker movie first hit the festival circuit, the festival snobs declared it to be an Oscar contender, and possibly the greatest comic book movie ever made. But when it got to the general public, who enjoy a steady diet of comic book movies, the response was much more polarized. There was a widespread campaign to boycott the movie over fears that its lead protagonist Arthur Fleck’s crusade against the rich could spark real-life incidents of violence. These fears turned out to be unfounded, as moviegoers realized the movie wasn’t as deep as the controversy suggested and no such incidents actually took place.

One of the main criticisms levied at Joker (by people who have actually seen it) is that it borrows heavily from existing movies. Phillips pulled together scenes and details and themes from a handful of Scorsese movies like Taxi Driver and Raging Bull and just replaced Robert De Niro’s brooding antiheroes with the Clown Prince of Crime. While The Killing Joke (the Joker’s most widely accepted origin story from the comics) was clearly a big influence on Phillips’ movie, he made it abundantly clear that he wasn’t interested in adapting the source material and instead wanted to offer a wholly original take on the character. But, while Arthur Fleck is original in the context of DC Comics history, he’s not original in the context of cinema, because his story has already been told much more effectively by Scorsese.

RELATED: David Fincher Has a Lot to Say About Joaquin Phoenix's Joker

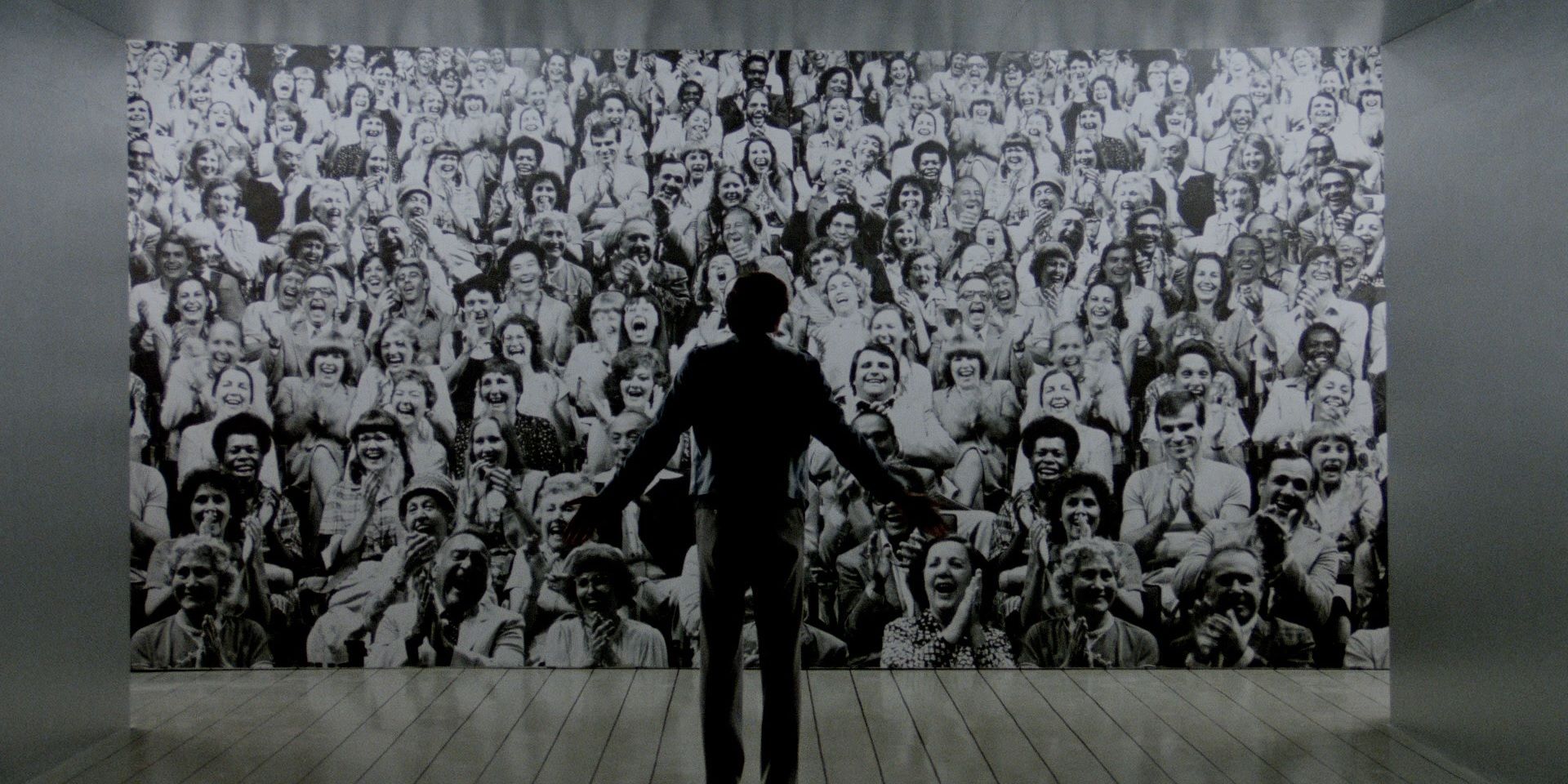

Although other movies certainly served as inspiration, The King of Comedy is the clearest jumping-off point for the Joker movie. One of Scorsese’s most underrated works, it’s a dark comedy masterpiece about a dangerously delusional aspiring comedian latching onto a famous talk show host and eventually taking him hostage to hijack his late-night show. Robert De Niro’s performance as Rupert Pupkin, a budding comic who will do everything to become a successful comedian except perform at an open mic night, is one of the best of his career.

Produced at the height of Scorsese and De Niro’s popularity (when they’d become disillusioned with celebrity), The King of Comedy is a bitter statement about the emptiness of fame. Rupert wants to skip past the hard work that goes into making it as a comic to enjoy the fleeting stardom that comes with one-in-a-million success. De Niro plays his delusions with such conviction that it’s hard to tell what’s actually real – and Scorsese leans into the ambiguity beautifully. Much like the ending of Joker (and the ending of Scorsese and De Niro’s own Taxi Driver), the final scene of The King of Comedy leaves it to the audience to decide how much of what they just saw was real, and how much of it took place in the protagonist’s head.

Like Arthur, Rupert lives with his mother. While Frances Conroy plays Penny Fleck on-screen in Joker, all of Rupert’s mother’s appearances in The King of Comedy are off-screen. Whenever she appears, she’s yelling at Rupert to keep it down, often interrupting the recording of his material (or his pretend talk show appearances with lifesize cardboard cut-outs of famous people) – much like Penny, she’s overbearing. The Arthur/Penny dynamic in Joker feels like a sanitized version of the much more memorable mother-son relationship seen in the far superior Joaquin Phoenix thriller You Were Never Really Here, directed by the great Lynne Ramsay. That movie is less on-the-nose about the specifics of the character’s trauma, but hits much closer to home with the emotions of it.

In The King of Comedy, Rupert kidnaps a talk show host in order to get one headlining spot to prove his mettle as a comic before gladly turning himself in to the authorities. In Joker, Arthur is invited onto a talk show after going viral (in 1981), then kills the host on the air. In both cases, the deranged aspiring comic commits a crime on live TV. Phillips even draws attention to the parallel by casting Robert De Niro as the talk show host. Murray Franklin is a lot more overtly obnoxious than The King of Comedy’s Jerry Langford, but the sentiment is the same. Both Rupert and Arthur are the little guy trying to get their foot on the ladder, and they’re incensed by seasoned pros Jerry and Murray looking down on them from the top.

The greatest tragedy of Joker ripping off The King of Comedy is that, even after Joker grossed over $1 billion with a watered-down version of it, it’s still underrated. It would be one thing if Joker’s success had led to The King of Comedy being brought into the mainstream four decades too late, but it remains one of Scorsese’s underappreciated gems alongside Bringing Out the Dead and Silence.

The themes of The King of Comedy ring even truer today than they did in 1982. Back in 1982, Rupert’s fame-driven mindset only applied to people who actively sought to be the next big movie star or a global pop sensation. Today, it applies to everyone posting their lives on social media. Social media has drawn millions of people into Rupert Pupkin’s relentless pursuit of attention and recognition. Not everyone is driven to a life of crime in their quest for likes, but the movie’s message about celebrity worship and the futility of chasing fame still holds up.

MORE: Zack Snyder’s Justice League: Why The Joker Meme Is Actually Very Important