The border of reality can be interpreted in many ways; borders between dreams and real life, borders between life and death. These ideas have been examined in films such as Ghost (1990), Spiral (1998), and The Science of Sleep (2006), to name a few. Ken McMullen’s 1983 experimental drama film Ghost Dance is significant in exploring the theories of ghosts; In Ghost Dance, the borders of reality are a barrier to not knowing what is real and what is in one's mind.

Ghosts are often referred to as real or of one’s imagination, and Ghost Dance delves into this phenomenon in a unique way that has not been done before. There seems to be no beginning, middle, or end to the story, and indeed that is precisely what this film highlights: memories that are never in the present.

RELATED: 10 Best Horror Movies With No Ghosts Or Supernatural Beings (According To IMDB)

Ghost Dance explores the myths of ghosts and memories, and philosophy plays a prominent role in these myths. In this film, philosopher Jacques Derrida looks at ghosts not as something supernatural but simply a memory of something which has never been present. The concept of cinema is discussed by Derrida, as he plays a ghost in the film. When interviewed for Cinema and Its Ghosts, he claims, “I think cinema, when it's not boring, is the art of letting ghosts come back.” Films, in general, are used as escapism or to make one see things differently than before.

Ghost Dance begins with a significant focus on the ocean, and throughout the film, water is a constant. The image of the ocean lingers for a long time as the tides rush in and out. This repeated elongated ocean image appears throughout the film. It almost serves as the one secure anchor among an ambush of scenes that speed by seemingly unattached to each other in non sequitur conclusions. The ocean is seen as the one thing that never changes; it was there when these ghosts lived, and it is there in the present as the spirits are resurrected.

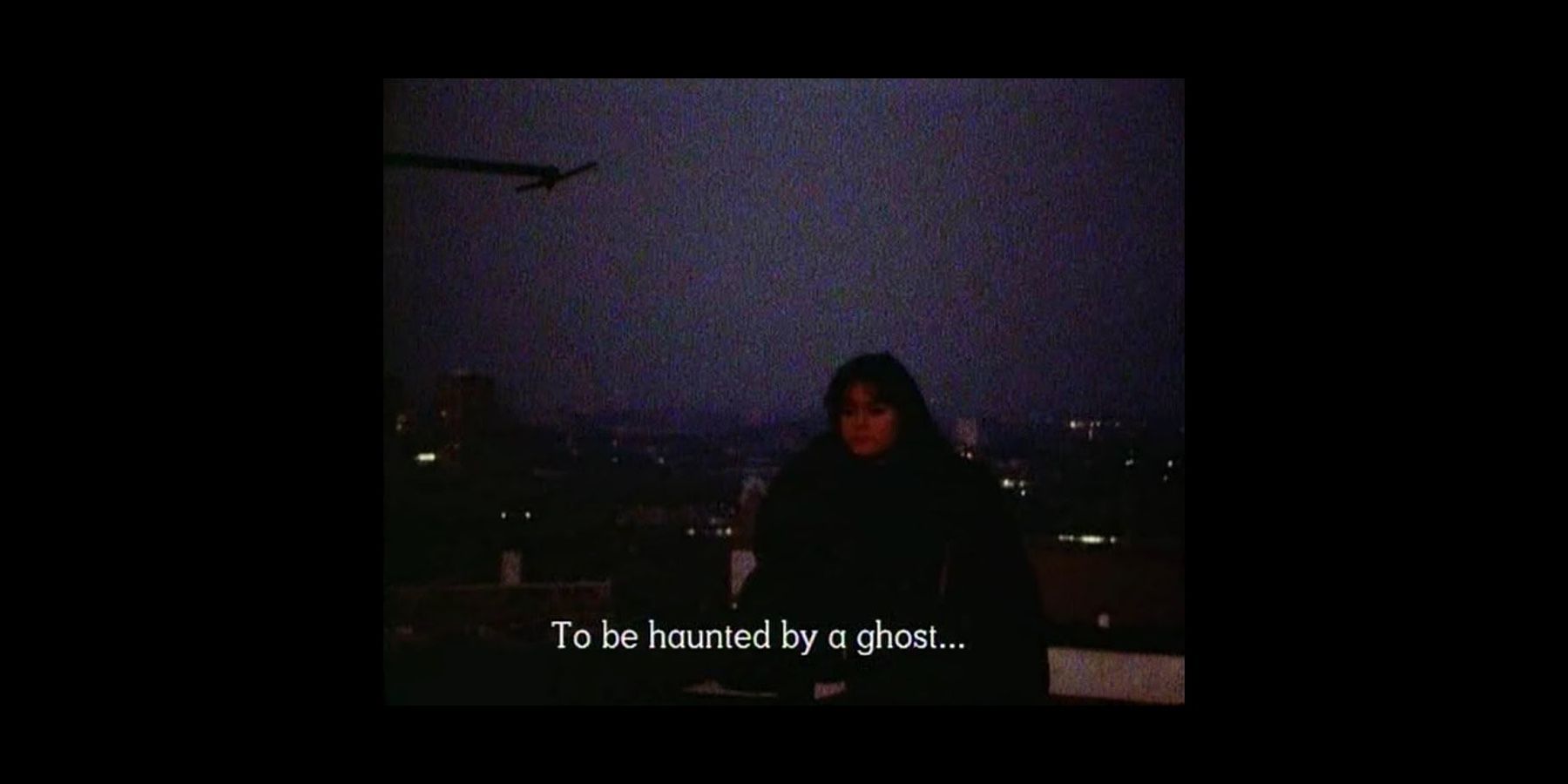

The film’s closest to a stable storyline is its focus on two women, Pascale (Pascale Ogier) and Marianne (Leonie Mellinger), as they wander through London and Paris. The cities seem bleak and desolate, perhaps symbolizing the starkness of the living, as the two women continue their quest for ghosts. As they walk around, Derrida speaks of different quotes that emphasize and illuminate their experiences. In one scene, Derrida walks along with the women, and he says, “Memory is the past that has never had the form of the present.”

Memories are actually pretty deceitful in their interpretation of the past. This is because they are thoroughly influenced by all the interconnected steps leading up to the actual present moment of remembering. Ghost Dance is edited in such a fashion to reflect this trajectory: the montage of scenes is connected in a non-linear manner as sequences come together but without any closure or reference to place and time. Some images are more potent than others and stand out on their own more powerfully, just as memories often do, but as a whole, they become synergistic.

Through a free movement of cinematography with minimal narrative and rambling of music, visuals, and voiceovers, the viewer is taken on a ride through images and sounds. These images almost look and feel hallucinatory, which adds a very palpable layer of physical absorption to a story entailing ghosts.

Just as cinema is used as escapism, Derrida believes that cinema taps into the minds and memories of those viewing. This film leads one to look at the past and understand that memories are not the harbinger of truth. Memories mesh together and distort what reality is. While the act of remembering something is in the present moment, the memory is not. This very act of presently recalling something from long ago in itself cannot be reliable due to the impossibility of separating the present circumstance one finds themselves in from the memory they are conjuring. The memory of the literal event has been altered by the time and distance of its actual occurrence.

Derrida implies the ghosts that occupy the theater aren’t just the ones that appear on the screen; the spectator projects their own ghosts onto the images they look at. He refers to these as “personal ghosts.” The border of reality in cinema requires certain techniques that disintegrate that wall of belief as it provokes a suspension of belief on the viewer's part. Films of fiction, fantastical storylines, and animation don’t allow the viewer to give up any refusal to accept that something is real or true. Much of the procedure to dissolve borders is in the editing process.

Ghost Dance ends as it began, with a minimalist scene delivering an image of the ocean; no narrative is conveyed as the tides come in more robust and more violently, swallowing the pictures and papers on the beach by Pascale. The ocean will own the lives of those who inhabit the photographs, which are phantoms of the real thing. This “slow cinema” approach to the entirety of the film enhances the enigma of the ghost. Still, this long take of the ocean ultimately reveals the mystery of life and the phantom of science. There is no resolution, only a constant revisiting to the sight of irresolution.

MORE: Zack Synder Shoots Down Rumor He’s Directing A ‘Ghost Rider’ Reboot